World Meeting of Families

Carolyn Y. Woo, “Faith, Family and Development: The Witness of Women in Leadership”

What does woman’s leadership look like? Carolyn Y. Woo, president of Catholic Relief Services, spoke on the second day of the Pastoral Congress at the Dublin World Meeting of Families (21-26 August). Her contribution, strongly rooted in the Chinese culture in which she was born and grew up, is based on three stories about women. “The first story concerns the women of my family,” she said. “Almost always, when we talk about leadership we think exclusively in terms of professional advancement. My mother taught me that leadership is the commitment to one’s family and marriage. I believe the family is the first and most important field in which to cultivate leadership.” Woo presented the story of the women in her family, starting from her grandmother, born 130 years ago in China “when the torture of the practice of tying feet was considered absolutely necessary for any girl who wanted to marry well.” When Woo’s mother was born, her grandmother made sure that this daughter would be educated and instructed by a tutor, who would teach her to read. Before the 1940s, Woo’s parents got married. “The marriage was a bit organized by my grandparents,” says the president of Catholic Relief Services, “My parents knew each other very little, they had met a few times without a companion, and both were under pressure because they had to get married. For Mom and Dad, escaping to the Chinese hinterland seemed the best alternative. Although they had very little in common, apart from their six children.” Woo explains that, in the Chinese culture of the time, the important thing was to have two sons: “an heir and a reserve.” “After four daughters and one son,” she recalls, “my father’s plan was to take a second wife (granted by law) if the fifth child was another female. And I came along. Fortunately, 18 months later a little brother arrived, and so my father did not take a second wife.” The marriage of the parents of the president of Catholic Relief Services was not a “happy” one by Western standards. “My father always took all the most important decisions and always raised my voice with my mother,” she recalls, “My mother, with her limited education and in a place like Hong Kong, very different from pre-war China, did her best to cope with the situation. She honed her extraordinary sewing skills to create western clothes for her daughters. She lined up to make sure we were enrolled in the best Catholic schools, even though she knew little about religion. With my aunt, she started a savings system, so that they could access emergency funds and small investment funds. My mother was not strong outwardly: she was often hesitant in the face of novelty and bureaucracy. Yet her presence, seasonal rituals, the stories of our ancestors, and the delicacy of our favorite foods made us feel like a family and, as such, we could overcome any difficulty, including my father’s heart attack, and the economic ups and downs. In difficult moments, Mother turned to the image of Our Lady, poured her worries out without speaking and found comfort.” From her mother, Woo learned the importance of education and, even more, the importance of feeling like a family and the strength that being a family can give. “She taught me humility,” she recalls, “Before I went abroad to go to college, she told me that I should never be too proud to take a broom and sweep the floor if it was necessary.” From his mother, Woo received the first leadership lesson: taking care of the house and the family, in which we find strength, a sense of belonging, devotion, and hope. The second story of leadership concerns my nanny, Woo continued; she came to work for our family and helped my mother take care of the children eight years before I was born. She stayed there for seventy years, until her death last February. She was 100 years old. As in the case of many working children, the nanny was sold at age eight to be a servant. She learned to read and write while listening to lessons given to her employer’s children. Although she was an extraordinarily beautiful woman, my nanny refused the marriage proposals she received, so she could continue sending her salary to her mother, who was widowed and looking after three other children.” At home, an agreement was made between little Woo, her mother, and the nanny. She would prepare me a perfectly ironed uniform, perfect pigtails, and a small box with a hanky,” she says, “For my part, I had to bring back a sticker of a bunny—that was the reward at school for work well done. A year of bunnies led me to my academic award.” Woo remembers how her nanny “had a keen sense of good and evil and pronounced her truths gently but firmly.” “In her work, she was a perfectionist,” she continued, “it was her way of honoring her responsibilities. Before becoming a Catholic in the nineties, she would kneel in the kitchen, in front of the window, as her morning began, thanking heaven and earth. My parents’ friends also had an important place in her heart. Her material poverty brought her great wealth of spirit. Like many women, she was an untitled leader, without formal power, wealth, and recognition. Yet, everyone who met my nanny improved; they learned new things and were touched by her generosity and integrity.” The third story of leadership proposed by Woo concerns the Maryknoll Sisters, where the president of Catholic Relief Services studied. Founded more than a century ago, the congregation of the Maryknoll Sisters was the first American missionary congregation. “From them, I learned not only English and literature, but also ideas and the ability to imagine a future different from that of our mothers,” said Woo, “we learned to support our ideas even publicly, with confidence and conviction, and were encouraged to recognize and nurture our talents.” Woo remembers how the Sisters prepared the girls not only “for professional success, but above all, they helped them to choose their vocation and pursue interests that gave them a purpose in life.” “I think that more than professional success,” Woo comments, “women’s success should be measured by the extent to which we are able to develop our gifts, use them, participate in the decision-making process, and be appreciated for these contributions.” The Maryknoll Sister taught Woo about the faith and the joy that comes from it. “From them, I learned about the power of faith,” she emphasizes, “The sisters never had everything they needed to start their projects, but that never stopped them. When they needed new funds to open a new school and the grants did not arrive, they were not discouraged: they stopped using public transport and walked.” “From them,” she concludes, “I learned the joy of serving people and God. Never in any moment of life, which they lived as in a family, did they lose hope; they were always happy and joyful, and this was because they had a deep sense of God’s presence. God’s work cannot be guided without Him. And with God, there is love, the power to move hearts, and the joy that keeps us going.”

23 August 2018

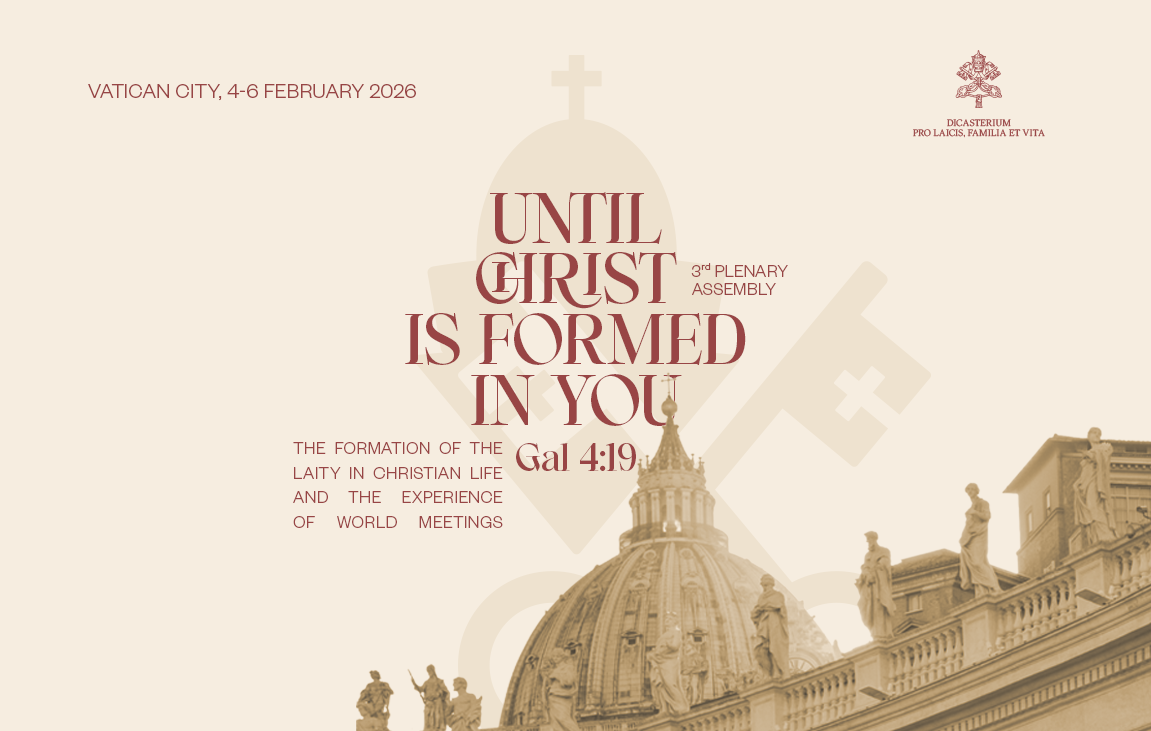

From 4 to 6 February, the third Plenary Assembly of the Dicastery for Laity, Family and Life

The third Plenary Assembly of the Dicastery ...

Read all >